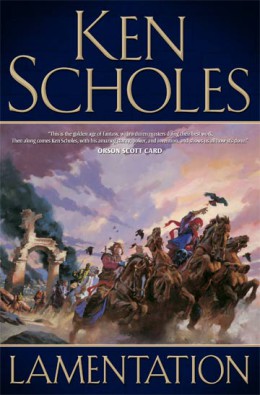

The following is Chapter Two of Ken Scholes’ debut novel—and the first volume in his series, The Psalms of Isaak—Lamentation, which hit bookstores on February 17. You can find the Prelude and Chapter 1 here.

Chapter 2

Jin Li Tam

Jin Li Tam watched the grass and ferns bend as Sethbert’s magicked scouts slipped to and from their hidden camp. Because her father had trained her well, she could just make out the outline of them when they passed beneath the rays of sunlight that pierced the canopy of forest. But in shadows, they were ghosts—silent and transparent. She waited to the side of the trail just outside of camp, watching.

Sethbert had pulled them up short, several leagues outside of Windwir. He’d ridden ahead with his scouts and generals, twitching and short tempered upon leaving but grinning and chortling upon his return. Jin Li Tam noted that he was the only one who looked pleased. The others looked pale, shaken, perhaps even mortified. Then she caught a bit of their conversation.

“I’d have never agreed to this if I’d known it could do that,” one of the generals was saying.

Sethbert shrugged. “You knew it was a possibility. You’ve sucked the same tit the rest of us have—P’Andro Whym and Xhum Y’Zir and the Age of the Laughing Madness and all that other sour Androfrancine milk. You know the stories, Wardyn. It was always a possibility.”

“The library is gone, Sethbert.”

“Not necessarily,” another voice piped up. This was the Androfrancine that had met them on the road the day before—an apprentice to someone who worked in the library. Of course, Jin Li Tam had also seen him around the palace; he had brought Sethbert the metal man last year and had visited from time to time in order to teach it new tricks. He continued speaking. “The mechoservitors have long memories. Once we’ve gathered them up, they could help restore some of the library.”

“Possibly,” Sethbert said in a disinterested voice. “Though I think ultimately they may have more strategic purposes.”

The general gasped. “You can’t mean—“

Sethbert raised a hand as he caught sight of Jin Li Tam to the side of the trail. “Ah, my lovely consort awaiting my return, all a-flutter, no doubt.”

She slipped from the shadows and curtsied. “My lord.”

“You should’ve seen it, love,” Sethbert said, his eyes wide like a child’s. “It was simply stunning.”

She felt her stomach lurch. “I’m sure it was a sight to behold.”

Sethbert smiled. “It was everything I hoped for. And more.” He looked around, as if suddenly remembering his men. “We’ll talk later,” he told them. He watched them ride on, then turned back to Jin. “We’re expecting a state banquet tomorrow,” he told her in a low voice. “I’m told Rudolfo and his Wandering Army will be arriving sometime before noon.” His eyes narrowed. “I will expect you to shine for me.”

She’d not met the Gypsy King before, though her father had and had spoken of him as formidable and ruthless, if not slightly foppish. The Ninefold Forest Houses kept largely to themselves, far out on the edge of the New World away from the sleeping cities of the Three Rivers Delta and the Emerald Coasts.

Jin Li Tam bowed. “Don’t I always shine for you, my lord?”

Sethbert laughed. “I think you only shine for your father, Jin Li Tam. I think I’m just a whore’s tired work.” He leaned in and grinned. “But Windwir changes that, doesn’t it?”

Sethbert calling her a whore did not surprise her, and it did not bristle her, either. Sethbert truly was her tired work. But the fact that he’d openly spoken of her father twice now in so many days gave Jin pause. She wondered how long he’d known. Not too long, she hoped.

Jin swallowed. “What do you mean?”

His face went dark. “We both know that your father has also played the whore, dancing for coins in the lap of the Androfrancines, whispering tidbits of street gossip into their hairy ears. His time is past. You and your brothers and sisters will soon be orphans. You should start to think about what might be best for you before you run out of choices.” Then the light returned to him and his voice became almost cheerful. “Dine with me tonight,” he said, before standing up on his tip toes to kiss her cheek. “We’ll celebrate the beginning of new things.”

Jin shuddered and hoped he didn’t notice.

She was still standing in the same place, shaking with rage and fear, long after Sethbert had returned whistling to camp.

Petronus

Petronus couldn’t sleep. He couldn’t fish or eat, either. For two days, he sat on his porch and watched the smoke of Windwir gradually dissipate to the northwest. Few birds came to Caldus Bay, but ships passed through daily on their way to the Emerald Coasts. Still, he knew it was too early for any word. And he knew from the smoke that there could be no good news, regardless.

Hyram, the old Mayor and Petronus’s closest friend from boyhood, stopped by each afternoon to check on him. “Still no word,” he told Petronus on the third afternoon. “A few City Staters said Sethbert marched north with his army to honor Entrolusia’s Kin-Clave. Though some are saying he started riding a full day before the cloud appeared. And the Gypsy King rallied his Wandering Army on the Western Steppes. Their quartermasters were in town buying up foodstuffs.”

Petronus nodded, eyes never leaving the sky. “They’re the closest of Windwir’s Kin-Clave. They’re probably there now.”

“Aye.” Hyram shifted uncomfortably on the bench. “So what will you do?”

“Do?” Petronus blinked. “I won’t do anything. It’s not my place.”

Hyram snorted. “It’s more your place than anyone else’s.”

Petronus looked away from the sky now, his eyes narrowing as he took in his friend. “Not anymore,” he said. “I left that life.” He swallowed. “Besides, we don’t know how bad things are.”

“Two days of smoke,” Hyram said. “We know how bad things are. And how many Androfrancines would be outside the city during the Week of Knowledgeable Conference?”

Petronus thought for a moment. “A thousand, maybe two.”

“Out of a hundred thousand?” Hyram asked.

Petronus nodded. “And that’s just the Order. Windwir was twice that easily.” Then he repeated himself. “But we don’t know how bad things are.”

“You could send a bird,” Hyram offered.

Petronus shook his head. “It’s not my place. I left the Order behind. You of all people know why.”

Hyram and Petronus had both left for Windwir together when they were young men. Tired of the smell of fish on their hands, eager for knowledge and adventure, they’d both become acolytes. A few years later, Hyram had returned home for a simpler life while Petronus had gone on to climb the ecclesiastical ranks and make his mark upon that world.

Hyram nodded. “I do know why. I don’t know how you stomached it for as long as you did. But you loved it at one point.”

“I still love it,” Petronus said. “I just love what it was…love how it started and what it stood for. Not what it became. P’Andro Whym would weep to see what we’ve done with it. He never meant for us to grow rich upon the spoils of knowledge, for us to make or break kings with a word.” Petronus’s words became heavy with feeling as he quoted a man who’s every written word he had at one point memorized: “Behold, I set you as a tower of reason against this Age of Laughing Madness, and knowledge shall be thy light and the darkness shall flee from it.”

Hyram was quiet for a minute. Then he repeated his question. “So what will you do?”

Petronus rubbed his face. “If they ask me, I will help. But I won’t give them the help they want. I’ll give them the help they need.”

“And until then?”

“I’ll try to sleep. I’ll go back to fishing.”

Hyram nodded and stood. “So you’re not curious at all?”

But Petronus didn’t answer. He was back to watching the northwestern sky and didn’t even notice when his friend quietly slipped away.

Eventually, when the light gave out, he went inside and tried to take some soup. His stomach resisted it, and he lay in bed for hours while images of his past rode parade before his closed eyes. He remembered the heaviness of the ring on his finger, the crown on his brow, the purple robes and royal blue scarves. He remembered the books and the magicks and the machines. He remembered the statues and the tombs, the cathedrals and the catacombs.

He remembered a life that seemed simpler now because in those days, he’d loved the answers more than the questions.

After another night of tossing and sweating in his sheets, Petronus rose before the earliest fishermen, packed lightly, and slipped into the crisp morning. He left a note for Hyram on the door, saying he would be back when he’d seen it for himself.

By the time the sun rose, he was six leagues closer to knowing what had happened to the city and way of life that had once been his first love, his most beautiful, backwards dream.

Neb

Neb couldn’t remember most of the last two days. He knew he’d spent it meditating and pouring over his tattered copy of the Whymer Bible and its companion, the Compendium of Historic Remembrance. His father had given them to him.

Of course, he knew there were other books in the cart. There was also food there and clothing and new tools wrapped in oilcloth. But he couldn’t bring himself to touch it. He couldn’t bring himself to move much at all.

So instead, he sat in the dry heat of the day and the crisp chill of the night, rocking himself and muttering the words of his reflection, the lines of his gospel, the quatrains of his lament.

Movement in the river valley below brought him out of it. Men on horseback rode to the blackened edge of the smoldering city, disappearing into smoke that twisted and hung like souls of the damned. Neb lay flat on his stomach and crept to the edge of the ridge. A bird whistled, low and behind him.

No, he thought, not a bird. He pushed himself up to all fours and slowly turned.

There was no wind. Yet he felt it brushing him as ghosts slipped in from the forest to surround him.

Standing quickly, Neb staggered into a run.

An invisible arm grabbed him and held him fast. “Hold, boy.” The whispered voice sounded like it was spoken into a room lined with cotton bales.

There, up close, he could see the dark silk sleeve, the braided beard and broad shoulder of a man. He struggled and more arms appeared, holding him and forcing him to the ground.

“We’ll not harm you,” the voice said again. “We’re Scouts of the Delta.” The scout paused to let the words take root. “Are you from Windwir?”

Neb nodded.

“If I let you go, will you stay put? It’s been a long day in the woods and I’m not wanting to chase you.”

Neb nodded again.

The scout released him and backed away. Neb sat up slowly and studied the clearing around him. Crouched around him, barely shimmering in the late morning light, were at least a half dozen men.

“Do you have a name?”

He opened his mouth to speak, but the only words that came out were a rush of scripture, bits of the Gospels of P’Andro Whym all jumbled together into run-on sentences that were nonsensical. He closed his mouth and shook his head.

“Bring me a bird,” the scout captain said. A small bird appeared, cupped in transparent hands. The scout captain pulled a thread from his scarf, and tied a knot-message into it, looping it around the bird’s foot. He hefted the bird into the sky.

They sat in silence for an hour, waiting for the bird to return. Once it was folded safely into its pouch cage, the scout captain pulled Neb to his feet. “I am to inform you that you are to be the guest of Lord Sethbert, Overseer of the Entrolusian City States and the Delta of the Three Rivers. He is having quarters erected for you in his camp. He eagerly awaits your arrival and wishes to know in great detail all you know of the Fall of Windwir.”

When they nudged him towards the forest, he resisted and turned towards the cart.

“We’ll send men back for it,” the scout-captain said. “The Overseer is anxious to meet you.”

Neb wanted to open his mouth and protest but he didn’t. Something told him that even if he could, these men were not going to let him come between them and their orders.

Instead, he followed them in silence. They followed no trails, left no trace and made very little sound yet he knew they were all around him. And whenever he strayed, they nudged him back on course. They walked for two hours before breaking into a concealed camp. A short, obese man in bright colors stood next to a tall, red-headed woman with a strange look on her face.

The obese man smiled broadly, stretching out his arms and Neb thought that he seemed like that kindly father in the Tale of the Runaway Prince, running towards his long lost son with open arms.

But the look on the woman’s face told Neb that it was not so.

Rudolfo

Rudolfo let his Wandering Army choose their campsite because he knew they would fight harder to keep what they had chosen themselves. They set up their tents and kitchens upwind of the smoldering ruins, in the low hills just west while Rudolfo’s Gypsy Scouts searched the outlying areas cool enough for them to walk. So far, they’d found no survivors.

Rudolfo ventured close enough to see the charred bones and smell the marrow cooking on the hot wind. From there, he directed his men.

“Search in shifts as it cools,” Rudolfo said. “Send a bird if you find anything.”

Gregoric nodded. “I will, General.”

Rudolfo shook his head. When he’d first crested the rise and seen the Desolation of Windwir, he ripped his scarf and cried loudly so his men could see his grief. Now, he cried openly and so did Gregoric. The tears cut through the grime on his face. “I don’t think you’ll find anyone,” Rudolfo said.

“I know, General.”

While they searched, Rudolfo reclined in his silk tent and sipped plum wine and nibbled at fresh cantaloupe and sharp cheddar cheese. Memories of the world’s greatest city flashed across his mind, juxtaposing themselves against images of it now, burning outside. “Gods,” he whispered.

His first memory was the Pope’s funeral. The one who had been poisoned. Rudolfo’s father, Jakob, had brought him to the City for the Funereal Honors of Kin-Clave. Rudolfo had even ridden with his father, hanging tightly to his father’s back as they rode beside the Papal casket down the crowded street. Even though the Great Library was closed for the week of mourning, Jakob had arranged a brief visit with a Bishop his Gypsy Scouts had once saved from a bandit attack on their way to the Churning Wastes.

The books—Gods, the books, he thought. Since the Age of Laughing Madness, P’Andro Whym’s followers had gathered what knowledge they could of the Before Times. The magicks, the sciences, the arts and histories, maps and songs. They’d collected them in the library of Windwir and the sleeping mountain village, over time, grew into the most powerful city in the New World.

He’d been six. He and his father had walked into the first chamber and Rudolfo watched the books spread out as far as he could see above and beyond him. It was the first time he experienced wonder and it frightened him.

Now the idea of that lost knowledge frightened him even more. This was a kind of wonder no one should ever feel, and he tossed back the last of the wine and clapped for more.

“What could do such a thing?” he asked quietly.

A captain coughed politely at the flap of the tent.

Rudolfo looked up. “Yes?”

“The camp is set, General.”

“Excellent news, Captain. I will walk it with you momentarily.” Rudolfo trusted his men implicitly, but also knew that all men rose or fell to the expectations of their leader. And a good leader made those expectations clear.

As the captain waited outside, Rudolfo stood and strapped on his sword. He used a small mirror to adjust his turban and his sash before slipping out into the late morning sun.

*

After walking the camp, encouraging his men and listening to them speculate on the demise of Windwir, Rudolfo tried to nap in his tent. He’d not slept for any measurable amount of time in nearly three days now but even with exhaustion riding him, he couldn’t turn his mind away from the ruined city.

It had been magick of some kind, he knew. Certainly the Order had its share of enemies—but none with the kind of power to lay waste so utterly, so completely. An accident, then, he thought. Possibly something the Androfrancines had found in their digging about, something from the Age of Laughing Madness.

That made sense to him. An entire civilization burned out by magick in an age of Wizard Kings and war machines. The Churning Wastes were all the evidence one could need, and for thousands of years, the Androfrancines had mined those Elder Lands, bringing the magicks and machines into their walled city for examination. The harmless tidbits were sold or traded to keep Windwir the wealthiest city in the world. The others were studied to keep it the most powerful.

The bird arrived as the afternoon wore down. Rudolfo read the note and pondered. We’ve found a talking metal man, in Gregoric’s small, pinched script.

Bring him to me, Rudolfo replied and tossed the bird back into the sky.

Then he waited in his tents to see what his Gypsy Scouts had found.

***